As one year comes to an end and another begins, many of us look back and reflect on the year. I think we are all happy to be done with 2020!

Nevertheless, my little flock of laying hens and my small herd of sheep provide daily leisurely joy and a degree of entertainment.

Both keep me busy. But it’s a busy we surely all enjoy.

As I’ve been reflecting, I began to think back over the years and ponder why it is that I became involved with keeping animals in the first place. It seems to have always been in my blood.

I have been on this planet for a few decades now, and I have been keeping chickens for a big part of that time, actually since I was just a young boy growing up in California’s Sonoma County, just north of San Francisco.

I grew up, for at least part of the time, with the rest of the family on my grandparent’s chicken ranch.

My grandfather kept around 20,000 laying leghorns on the home ranch and two additional rented properties. While that may sound like a lot, most of the properties around us had similar operations.

Sonoma has now switched to dairy and wine country, with only a few of the original poultry operations still in business. Still, make no mistake, it was chickens that put my hometown of Petaluma on the map and set me on my life path.

Panning for Food

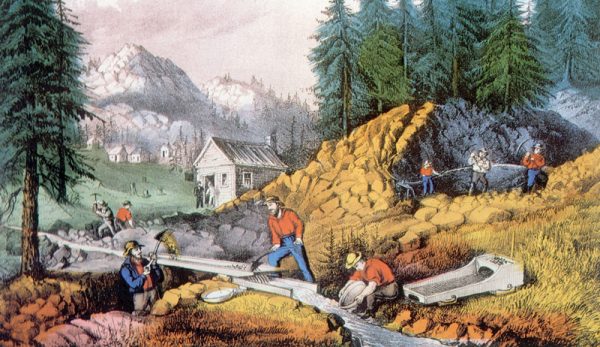

It all started for California because of the discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada Mountains east of Sacramento. The discovery was early in 1848 and precipitated the Gold Rush of 1849.

California became a state the following year in 1850, and the boom was on. Thousands of immigrants moved to California with the idea of striking it rich. Very few did.

A gold pan that cost 20 cents before 1849 could be sold for $8 after gold was found. A single egg might cost a miner $2 in a mining camp. Adjusted for inflation that would be a $50 egg and a $200 gold pan!

The prospectors that were finding gold and had good claims could actually afford those kinds of prices. But the vast majority had to move on as the gold fields and streams became less reliable.

Most moved to Sacramento, San Francisco and California’s Central Valley to make a living as farmers. Some that had the capital opened hardware stores or sold tack, provisions and/or clothing. Those early entrepreneurs were the ones that eventually became wealthy.

Primed for Poultry

As you consider the previous framework of events, let us take a look at how food crops, the livestock industry and the poultry industry, in particular, evolved to meet the needs of all the new inhabitants.

With an infusion of well over 100,000 new immigrant settlers, it’s pretty obvious that the food supply would be lagging far behind. With demand high and supply low, prices always skyrocket. Thus, the shortage of food actually became an opportunity for those capable of production.

San Francisco is just south of the Golden Gate Strait, and the Sacramento River runs beside Sacramento. Both cities are accessible by water and boats. But the Golden Gate Bridge wasn’t in service until 1937.

In the early days, red meat, poultry and eggs were shipped up the rivers to points inland. The situation became so perilous that eggs from nesting shore birds were actually robbed from the cliffs on the Farallon Islands about 20 miles off the San Francisco coast.

Settlers that had land to the north, near a little town called Petaluma, started raising crops, beef cattle, sheep and chickens so that products could travel via steamboat down the Petaluma River in Sonoma County.

Even so, the farmers and ranchers 18 miles up the river from San Francisco Bay couldn’t keep up with demand. Production had to find a way to meet demand, because even well after the gold rush, California’s population continued to soar.

Read more: Odd eggs? Here are a few unconventional yolks you might find in the nesting box!

Golden Eggs

It seems that whenever there is a huge need, someone steps forward to solve the problem. So it was in 1879 that an immigrant from Ontario, Canada, who was living in Petaluma, invented the first successful incubator.

Lyman Byce was one of 10 children. He invented a redwood box incubator that utilized a coal oil lamp as the heat source. The eggs

had to be rotated by hand three times per day for 21 days. But thanks to Byce, the little towns of Petaluma and Two Rock (to the west) soon became known as the “Egg Basket of the World.”

The early Byce incubator was not as efficient as a modern electric incubator. But hatcheries began to spring up and produce large numbers of laying hens to help meet California’s demands. Byce’s incubator could hatch 400 eggs with a 95 percent success rate.

The electric incubator, invented later in Ohio, didn’t hit the poultry scene until 1922. By that time, the little river town of Petaluma was one of the wealthiest towns in California. Thanks to the poultry industry, Petaluma even survived rather handily during the Great Depression.

During the height of the poultry boom in Petaluma, hundreds of producers such as my grandfather existed. Petaluma had dozens

of hatcheries selling day-old sexed chicks hatched from old redwood incubators and, in the heyday, from electric units.

Dozens of producers also specialized in selling 2-month-old started pullets

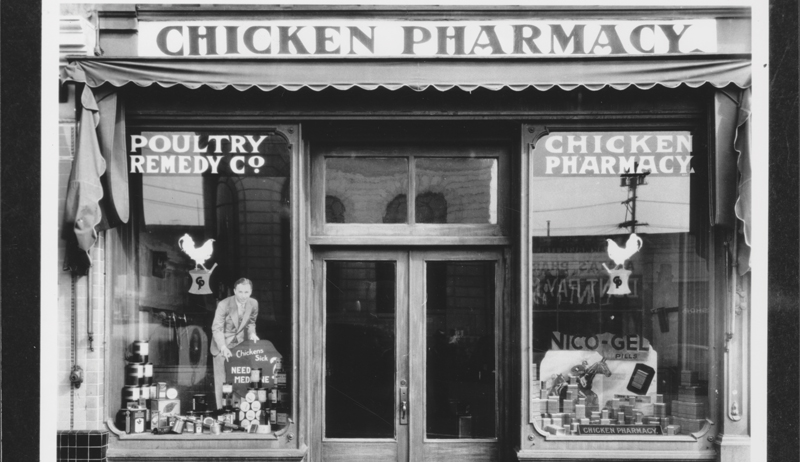

There were a half-dozen feed-milling companies, numerous feed stores and even an oyster shell company selling crushed oyster shells from the nearby coastal oyster beds. At one point, Petaluma even had a poultry pharmacy! The pharmacy is listed in Ripley’s Believe It or Not and sold as many as 50,000 poultry medications in pill form in a single day.

Those early feed mills began expanding and making feed products for the dairy industry. My late father went to work for a cheese factory and eventually to the construction trades.

The chicken culture slowly gave way to dairy and wine.

Staying Alive

To be sure, Petaluma’s agricultural past has never died. Most family-owned mills live on, in some form or another.

Names such as Golden Eagle Milling, McNear, Vonsen, Epping, Lewis and Ash have stayed in business but have shifted gears and successfully modernized.

Some of them merged and moved away. Some have stayed but have changed their company names.

George P. McNear and Golden Eagle Milling are long gone, but the brick and mortar structures can still be found along the river where they once loaded steamboats. The buildings that have survived have been converted to walk-in specialty stores. They are great historical spots to visit.

I am pretty sure there are no hatcheries still operating in the little river town. However, there are a couple of creameries bottling milk nearby.

Still Clucking

To this day, Petaluma celebrates Butter & Eggs Days each spring with a huge celebration and parade. Just 40 miles north of San Francisco on Highway 101, Petaluma has a farmers market to die for. No vacation to the San Francisco Bay area is complete without a quick stop in Petaluma.

I am very proud of my birthplace and the impact it has had on our country’s agriculture. I am even happier to see all the small operators and enthusiasts all over our country raising chickens, sheep and other farm animals in open pastures.

It makes me feel like the past is still alive.

A few years back, I built my own henhouse with the idea of copying the little colony houses my grandfather had freestanding in his pastures.

My henhouse adds just a bit of nostalgia to my backyard. My chickens can access their run and my 12-acre almond orchard out the back door. Obviously, the designs that worked for laying hens more than 100 years ago still work well for the hens of today.

Read more: Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletters!

Sidebar: Free-Range Futures

It saddens me to think of how today’s commercial producers keep laying hens in confinement with minimal space. In 2008, California passed Proposition 2 with the intent of improving confinement conditions.

Indeed, tight quarters for laying hens have improved across the U.S., but in the early days (when I was a youngster), chickens were kept in high-fence pastures and often with sheep or other livestock. The hens had rows of small colony houses that provided roosting boards and nest boxes.

Chickens spent most of the day outside in the pasture.

The colony houses were starting to disappear when I was a boy, because gathering hundreds of eggs from each little 10-by-12- foot house was time-consuming. Sometimes hens would simply lay eggs in the pasture.

Later, we built long redwood henhouses that housed many more hens. The long houses that everyone began to use had wood floors and long but narrow adjoining rooms with as many as 500 leghorn hens per room.

For feeding and egg gathering, the longer houses reduced labor. All the hens still had access to the outside during the day.

As a schoolboy, I rode the bus home in early afternoon and helped with feeding and gathering eggs. My grandfather had a large commercial egg-washing and sorting machine. The washed and dried eggs were put in flats that held 2 1⁄2 dozen eggs.

Everything was done by hand.

All the hens were of the Leghorn breed and all the eggs were typical of the white-shelled eggs you see in grocery stores today. It might sound funny, but I was about 12 years old before I ever saw a brown egg. I didn’t even know they existed!

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2021 issue of Chickens magazine.